Working to balance short-term plans with a long-term vision for I-275

A grassroots plan to replace a stretch of I-275 in Tampa with a boulevard is gaining traction as the FDOT mulls multibillion dollar projects along other areas of the corridor

Josh Frank wants to clear up a misconception. He is not pushing for construction crews to go out tomorrow, or anytime soon, and tear up a roughly 11-mile chunk of Interstate 275 in Tampa.

But Frank, a Tampa Bay Area urban designer, is promoting a long-term vision that would indeed replace the congested stretch of I-275 from Pasco County to the “Malfunction Junction” interchange with I-4 in downtown Tampa with a local boulevard carrying cars, trucks, buses, pedestrians, cyclists and light rail.

After more than two years pounding the pavement to present the idea to neighborhood groups, civic organizations, and government bodies, Frank’s concept is beginning to gain traction.

The local elected and appointed officials on the Hillsborough Metropolitan Planning Organization board have put money in the budget plan for their upcoming fiscal year to study the feasibility of replacing that stretch of I-275, which runs through neighborhoods such as Tampa Heights and Seminole Heights, with a boulevard design.

But boulevard advocates’ excitement over that development is tempered by some other plans the Florida Department of Transportation and the MPO board majority have advanced for a portion of that stretch of I-275.

To deal with existing congestion, they plan to add a travel lane in each direction from Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard. to Bearss Avenue, along with noise walls and hardened shoulders for express buses, and add a lane to the flyover from I-275 to I-4 — all within existing right-of-way.

It is a far more scaled-back plan than the tolled express lanes FDOT previously proposed, and then dropped in the face of public backlash, along I-275 north of I-4, as part of TBX, the planning process for I-275 improvements that has since been rebranded Tampa Bay Next. The current plan is also significantly stripped down from the multibillion interchange reconstruction at I-275 and I-4 proposed in Tampa Bay Next — a project FDOT officials say they have no intention to pursue anytime soon as they focus instead on first the replacement the Howard Frankland Bridge and then widely supported improvements at and around the Westshore interchange.

Still, Frank and boulevard advocates say the interim plans now on the table to add lanes follows an often-unsuccessful strategy of trying to build your way out of congestion. Frank feels that strategy falls victim to the theory induced demand — widen a roadway to get out of congestion and more drivers arrive to fill it up.

Boulevard advocates want a more albeit longer-term vision that improves transit, bicycle/pedestrian facilities, and the connectivity of the city street grid to get vehicles off the interstate.

For his part, Frank says he sees headway in the debate despite the MPO vote last week to push forward with additional lanes.

“The meeting was great progress in the overall conversation this community has had regarding a shared desire for transit alternatives,” he says. “Unfortunately, we’re not there yet, but more people today understand that expanding interstate capacity only creates more congestion. And that is a success. Having said that, expanding the interstate should be last in our priorities. We should aspire to do better by building transit first and actively work to remove cars from our roadways — the only real solution to congestion.”

At the same time, the interim improvements on I-275 are not an either-or proposition with studying the boulevard concept further, MPO Executive Director Beth Alden says.

“This would obviously be a long-range proposition — it could take decades to do feasibility studies, create engineered plans, and line up hundreds of millions of dollars for construction – and so this study is no reason not to move forward with some modest fixes for immediate problems on this portion of I-275,” Alden writes in an email.

An idea born from “community revolt”

For Frank, the chain of events leading to the boulevard concept starts at the University of South Florida. As a graduate student at the USF School of Architecture & Community Design, he was asked to help with the community engagement process for TBX, the predecessor to Tampa Bay Next that included tolled express lanes north of I-4 and required a significantly larger amount of properties for right-of-way.

“The community really revolted and upset that process,” he recalls. “That was really a profound thing.”

For his master’s thesis in urban and community design, he decided to look for solutions to that public opposition in the form of potential alternatives to TBX. Looking at the situation from an academic and design perspective, he pursued the boulevard concept.

“This is a purposefully ambitious proposal because this is where we need to get,” Frank says. “The thought is we are growing in a way that is unsustainable. The corridor is already as wide as it’s going to get. If you widen it, it’s just going to fill up. We are at a point where we have to start thinking hard about getting cars off that corridor. The planning, design, and construction of transportation alternatives to allow for that has to happen through other local agencies. That is a process I am hoping the upcoming study will start. We need to start establishing goals.”

Tampa’s new spine

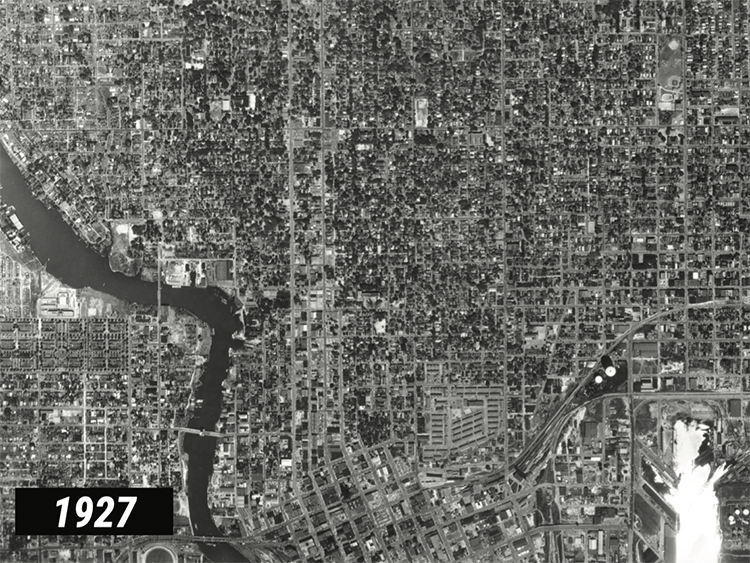

I-275 dates back to the 1960s. Its construction, like many interstates, ran through and divided existing neighborhoods, including once thriving minority communities. Intended to carry regional traffic, the road now carries a fair share of local commuters- and a total of some 170,000 daily vehicle trips in some areas north of I-275.

“People who are using it are using it incorrectly,” Frank says. “I-275, and all interstates, were built as throughways to connect suburban and rural areas further away from the urban core to their employment centers and tourist destinations, airports, ports — all those sorts of things. The problem is: We’ve grown up. Tampa has grown significantly since the 1950s, and what was once the edge of town at Sulphur Springs and the Hillsborough River is now the middle of our city.”

His working concept, which he sees as a starting point for a needed conversation, is to replace I-275 from the I-75 junction in Pasco County to I-4 with a six-lane boulevard with a dedicated lane for light rail or mass transit and bicycle/pedestrian paths.

Regional traffic would continue down the boulevard, take another north-south route or take I-75 to I-4 and then come down I-4 to the stretch of I-275 south of the boulevard.

Frank feels that removing the interstate would reconnect neighborhoods, improve street connectivity, promote alternative transportation options including mass transit, ease congestion on side streets leading to the interstate, and open up some dozens of acres of land now in the interstate’s footprint for redevelopment that goes on the tax rolls. People living near the interstate would have improved quality of life from reduced noise and air pollution, he says.

Precedents are out there

Frank acknowledges the concept is foreign to FDOT, the state of Florida, and the Southeast. But there are precedents out there in other areas of the United States. In the years after the 1989 San Francisco earthquake, two damaged freeways, the Embarcadero and Central, were demolished and replaced by boulevards in projects that included transit and park construction, according to the Urban Land Institute.

In the 1970s, Portland’s Harbor Drive freeway was replaced with a boulevard for local traffic and a waterfront park, spurring economic development in the city’s downtown, the Congress for New Urbanism notes.

In Milwaukee, the demolition of the elevated, unfinished Park East Freeway reconnected areas of the city and opened up land for redevelopment.

In Seattle, the long-planned, ongoing demolition of the Alaskan Way Viaduct has investors buying up land in the area with an eye toward redevelopment, the Seattle Times reports.

Alden, the Hillsborough MPO executive director, notes that Dallas is looking at digging a trench for its interstate to open up the area above for mixed-use redevelopment. She says the MPO study could look at that option for I-275, including whether it is feasible or realistic with the Tampa Bay area’s water table.

FDOT’s plans

David Gwynn, FDOT District 7 secretary in Tampa, has told the MPO that the Florida Department of Transportation is not opposed to studying the boulevard concept. But he says it is an “extremely complicated process” that will have to include other regional governments, provide mitigation steps to accommodate traffic removed from the interstate, identify alternative evacuation routes and funding, and, eventually, get a green light from the Federal Highway Administration.

In response to the same public input that led Frank to propose the boulevard concept, FDOT itself eliminated plans for toll lanes north of I-4, reduced the footprint of the planned improvements at the I-4/I-275 interchange, and decided bus rapid transit or express bus lanes will have use of the express toll lanes included south of I-4 and in the Westshore area.

The agency is also looking at potential improvements on roadways near the interstate in Tampa Heights, Seminole Heights, East Tampa, and West Tampa, and has made securing funding for the widely supported Westshore area interchange projects the priority after the Howard Frankland replacement.

A long-term vision

Frank says a lot of things have to fall in place for the boulevard plan to become reality. They include more transit routes with faster service, improved travel flow on alternate north-south routes in Tampa, and possibly a light rail system on the CSX rail line. Some projects to provide an alternate route, such as the Selmon Expressway extension in the Gandy Boulevard area, are already underway.

“The ultimate goal of this is not to replace the interstate tomorrow but to start that conversation,” Franks says. “It’s not just the interstate; it’s transportation in the entire region. We can do better than this.”

Here are links to some of the plans and organizations in the story Tampa Bay Next, Boulevard Tampa, the Hillsborough Metropolitan Planning Organization.

Here is additional information on other freeway removal projects in San Francisco, Seattle, Portland, and Milwaukee.