Ocean Team: USF Marine College Interprets Sounds From The Deep

The University of South Florida College of Marine Science is the centerpiece of a growing hub of marine-related organizations dubbed the Ocean Team by the City of St. Petersburg. The small graduate-level college sees its role as a steward of the oceans, sending scientists out globally to study important environmental issues.

The Deep Horizon oil spill in 2010 catapulted the USF College of Marine Science onto the national radar screen as scientists became a voice of authority on how the toxic fallout is affecting the Gulf of Mexico. But that is only one of many important projects underway here.

Red tide, climate change, ocean acidification, hurricane predictions, overfishing and coral reef destruction drive marine scientists to find answers. David Mann, Ph.D., leads a team exploring underwater sounds to learn more about marine life.

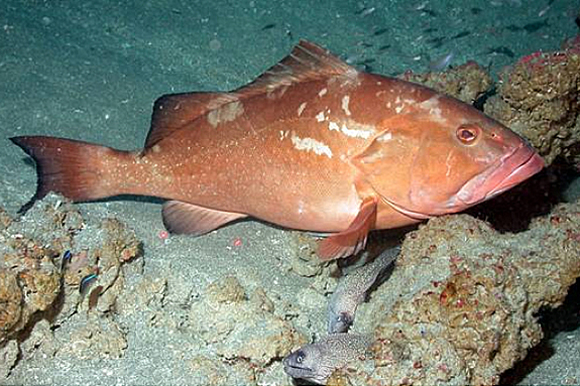

Most people are aware that dolphins communicate through a series of squeaks and clicks. But who knew that damsel fish purr, grouper and red hind growl, cusk eels create a staccato noise like a jackhammer and the metallic ping from clownfish is like a drum stick hitting the rim of a snare drum?

It may not always be pretty to human ears, but there’s definitely a lot of fish vocalization happening underwater on the West Florida Shelf, a relatively shallow body of water that extends about 100 miles off the coast of the Gulf of Mexico from the Panhandle to the Keys.

In fact, a New York Times article in 2005 reported that fish sounds from the mating call of the black drum fish were keeping residents of Cape Coral in Southwest Florida awake at night.

Mann was one of the experts called in to confirm that the nightly low-throbbing bleat coming from the waterway canal system was in fact a fish, the “Barry White of Fish,” as the male black drum has been called.

Mann is an expert in bioacoustics, the science of sound. He has been studying fish vocalization since graduate school. He earned his doctorate through a joint program between the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts. These days, he and his team at the USF College of Marine Science, where he is an associate professor, are listening to all the underwater chatter off the west coast of Florida.

Eavesdropping From Above

By analyzing the sounds that fish make, Mann hopes to learn not only who’s making the sounds, but where they’re located, what they’re doing and how many there are. “A lot of scientists are looking at the sound of marine mammals, but not as many are looking at fish, says the St. Petersburg scientist.

Not every fish makes sounds. But those that do have their own distinct frequency and vibration that is species specific. Unlike dolphins, which have a high-frequency pitch, fish sounds are always in the low-frequency ranges — you might describe it as the sopranos versus the baritones.

Recognizing species-specific sound patterns is the key to Mann’s ability to map their distribution over the Gulf. Then he hopes to take that data and extrapolate population size and demographics like the location of fish spawning areas and knowing when spawning will occur so the eggs can be protected.

Making the leap from collecting recordings of fish vocalization to something concrete presents a challenge, he admits, but until scientists can complete long-term measurements of fish populations, it will be difficult to answer questions related to environmental issues, such as predicting whether a population drop might be due to massive over-fishing or some environmental toxin.

“Think of the ocean as a frontier that is so big and hard to work in,” says Mann. “The goal is to understand how the whole ecosystem works.”

Feeding Florida’s Economic Engine

Unraveling all of these mysteries can also come down to a matter of economics. One of the fish Mann’s team is currently mapping is the red grouper, prized by the fishing industry for the high value its tender white flesh brings. This is the fish used in the famous Florida grouper sandwich. There are billions of dollars at stake here. Knowing more about the species is vital.

“The Gulf is extremely important economically for both commercial and recreational fishing,” says Bill Hogarth, former USF Marine College dean and now executive director of the Florida Institute of Oceanography. The National Marine Fisheries Service estimates the commercial fish and shellfish harvest from the Gulf to be 1.3 billion pounds, equal to about $661 million.

But to Mann, the study of bioacoustics is also a matter of pure scientific curiosity.

“The Gulf of Mexico is my backyard,” he says. “There are a lot of things we don’t know and a lot of surprises out there. For example, we have catalogued several unknown sounds that are produced over large areas of the Gulf, but as of yet, we don’t know what type of fish they are. It’s cool that there are sounds we can hear but we don’t know what is making them.”

In the past few years, Mann’s team has amassed thousands of hours of acoustic recordings, primarily through deployment of hydrophones and ocean gliders, a type of underwater device that uses buoyancy as a means of propulsion. He says the next task is to develop a computerized method of going through the data and automatically picking out sounds and classifying them. And then perhaps moving from mapping the West Gulf Shelf to the entire Gulf of Mexico and then to the East Coast of Florida.

Janan Talafer is a St. Petersburg-based freelance writer with a passion for swing dancing, tropical gardening and yoga. She shares a home office with her faithful cats Milo and Nigel and her dog Bear. Comments? Contact 83 Degrees.