Hillsborough schools, community nonprofits innovate to improve childhood literacy

Hillsborough County Public Schools, Hillsborough Education Foundation, and community nonprofits funded by the Children's Board of Hillsborough County are using innovative approaches to improve childhood literacy.

Nearly half the school children in Hillsborough County currently read below grade level, but educators are excited about a new method of teaching that seems to be making a difference.

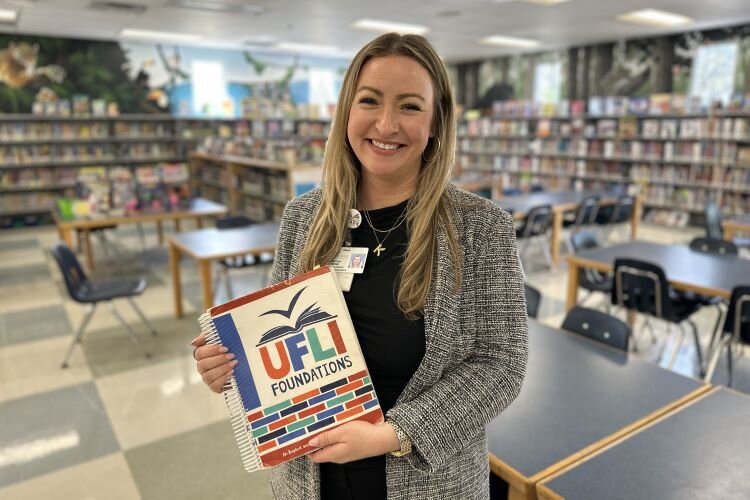

Developed by the University of Florida Literacy Institute, the method, called UFLI Foundations, has been used by the school district for two years to teach reading to kindergartners, first and second graders, and as a remedial lesson for struggling readers in third through fifth grades.

Educators want to have all students reading on level by third grade. As Hillsborough Education Foundation’s website puts it, students are learning to read up to third grade, when they shift to reading to learn.

“Students are thriving on this routine and this procedure and this explicit nature of instruction and really becoming readers,’’ says Hillsborough County Schools’ district literacy coach Kaitlin Powers Behn, who teaches students and coaches teachers how to use the method.

Allison Trela, mother of second-grader Joseph and kindergartner Penny, is impressed by the new teaching technique.

“I see a huge improvement in Penny,” she says. “She went from not reading to sounding out words, not guessing. I feel it’s given her the confidence to be a strong reader.’’

Last year, Joseph went to a private school that did not teach the UFLI method, Trela says. He’s always been a fairly strong reader, but after being exposed to the method just this year, he’s already reading on a third-grade level.

“So it’s above the grade he’s currently at, which is huge,’’ she says.

Learning through instruction and practice

The UFLI method is an eight-step program that teaches phonics in a systematic way. Students learn the letters and the sounds they make and have to voice them in drills. They learn to blend the sounds of letters, write the words, and place them in sentences.

It’s instruction with a lot of time for practice, Behn says, with the goal of having students look at combinations of letters and automatically know the words.

The 2025 State of the Region report for the Tampa Bay area, compiled by the Tampa Bay Partnership in collaboration with Community Foundation Tampa Bay and United Way Suncoast, states that kindergarten readiness scores improved 1.83 percent since the previous year’s report, from 50.28 percent to 52.11 percent. Third-grade reading improved significantly, from 47.70 percent to 53.57 percent, a 5.87 percent boost.

The way reading is taught has changed over the years. Hillsborough Assistant Superintendent of Curriculum and Instruction Tracie Bergman notes that in the 1950s,’60s, and into the ’70s, kids learned to read by phonics.

“Then the pendulum shifted to whole language, and the theory became more along the lines of kids will just learn their foundational skills with exposure to lots of text,’’ she says.

Teachers read aloud to students, gave them text to follow along, and taught them strategy on how to look at words and guess words, Bergman says.

“They didn’t have explicit instruction and foundational skills,’’ she says, “so our youngest kids were not getting phonic skills. They were getting guess-my-word skills.’’

With the whole text method, for example, a child might read the word “horse” as

“pony” because the picture with the text shows a “horse-ish, pony-ish thing,’’ Bergman explains.

“I call it a pony and the book says horse. Is it that big of a deal for reading? Probably not,’’ she says. “But is it a problem that I couldn’t read the word “horse”? Yeah, it’s going to be a problem, especially when there aren’t any pictures when I get into my upper grades and I don’t know how to decode, and I’m not paying attention to the letters. I learn how to guess words, and as I get older I guess words wrong.’’

Educators went back to teaching phonics, but not in a systematic way. Now, with UFLI, the district’s primary grades are getting explicit, systematic foundational skills instruction. To make sure the students grasp this method, they’re tested to see if they can hear individual sounds of letters in words, read words in sentences, and read even nonsense words.

The results of the first year under the UFLI method showed that the majority of first graders who were tested at the beginning of the school year were tracked at proficiency levels that matched where they were when they ended the year in kindergarten.

“We’re tracking our kindergartners who are now in first grade,’’ Bergman says. “This is year two for them. We’re actually seeing huge gains compared to where they entered kindergarten… Right now our first graders, from the beginning of the year data, tracked at proficiency levels that matched where they ended the year in kindergarten. So we continue that trend. We ended with about 57-58 percent of them proficient.

“So if we can continue that trend and start that way in first grade, we’re excited to see where we can end the year with these first graders. If we’re starting where we ended (in kindergarten), that’s pretty cool, because that means that they held onto their learning from last year and they can only accelerate from there.’’

Helping struggling readers

Hillsborough Education Foundation is pitching in on the effort with its Transforming Early Learning Initiative, using the UFLI method, and concentrating on 14 elementary schools where more students are struggling with reading.

Hillsborough Education Foundation President and CEO Anna Corman says the initiative uses literacy coaches who are school district employees and experts in teaching early literacy.

“We identify schools that are Title 1,’’ she says, “and also look at schools that had not so great reading scores, and then schools that have a high percentage of

minority students enrolled, because we know that those students are, unfortunately, impacted a little bit more.

“So we picked these 14 schools to work with and these literacy coaches work directly with those schools,’’ she says.

The coaches work with students and also teach the teachers how to use the UFLI method, focusing resources on pre-kindergarten and kindergarten students to try to prevent literacy struggles from ever becoming an issue.

“That’s been our model, providing job-embedded professional development for teachers so that they have the skills and resources and feedback and connection with professionals to be better teachers in early literacy,’’ Corman says.

This approach is intended to make the process less cumbersome for teachers.

“We noticed that a lot of teachers were being asked to go to professional development to get these skills on weekends and in the evening, and often that’s unpaid,” Corman says. “So we decided we could do literacy coaches and make this job-embedded. Then it’s not one extra thing to do, it can just become part of their practice.’’

Because parents also need to be working with their children, teachers are also provided resources to help them engage families, she says. Schoolchildren need to be exposed to books and word-enriching activities as early as possible, Corman notes.

Foundation for a child’s success

The Children’s Board of Hillsborough County helps fund multiple nonprofit agencies that have programs focused on reading skills.

“Reading proficiency is the foundation for a child’s success in school and beyond,’’ says Children’s Board Executive Director Rebecca Bacon.

“When children develop strong literacy skills early, they gain the confidence and ability to explore new ideas, communicate effectively, and thrive in their education,” Bacon continues. “At the Children’s Board of Hillsborough County, we are committed to supporting families with resources that foster early literacy, ensuring every child has the opportunity to reach their full potential.”

Hillsborough Community College’s Quality Early Education System, funded by the Children’s Board and Helios Education Foundation, concentrates on preparing preschool children for kindergarten. QEES, as the program is called, works with nearly 1,000 children in about 200 preschools in the county, says Program Director Marni Fuente.

“All of my coaches, they go into the schools every week and they work with the children in small groups in the classroom alongside the teacher,” Fuente says. “So they’re modeling for the teacher while they’re working with the children. And then we also have parent workshops and parent training as well.”

QEES has four components: QEES Pathways, offering continuing education and on-site coaching on the foundations of early childhood education; Early Literacy Matters, ongoing training for teachers and parents; Business Management & Operations Team, providing support and services focused on operational management practices to all licensed child care facilities and homes; and CALM, which provides training to early education providers and parents in social-emotional learning.

“We come in and have to do activities to unite,” Fuente says of the CALM program. “We want to make everyone feel welcome and that they are a part of the school… We want to help them disengage stress. So we teach them activities, whether it’s taking a deep breath. We set up safe places where children can go and sit and just take a minute for a pause. It’s not a time-out; this is someplace where it’s okay to feel that upset. We give them permission to feel their feelings, but then identify the why and how can we do this better next time.’’

The preschoolers are taught compassion and empathy and how to “communicate the needs in a mindful way,’’ Fuente says.

“We have to learn to calm ourselves down, to take a deep breath and find the tools that will help us get calm, before we can take the next step to solving problems, to learning,’’ she says.

For more information, go to Hillsborough Education Foundation Transforming Early Literacy, Hillsborough County Public Schools Literacy, Children’s Board of Hillsborough County, and QEES