Dobyville residents revive history of Hyde Park’s historic Black neighborhood

Residents living in an area once named for a successful Black businessman, Richard Doby, are seeking local historic district protections for the Hyde Park community.

When Tara Nelan first saw the house at 1405 W. Azeele St. on Google Maps, it looked adorable. She decided to buy it.

She had no idea it was once the home of Richard Doby, a successful Black ice dealer and real estate investor after whom the community of Dobyville was named. That is, until a neighbor told her after she bought the house in April, 2020.

“I felt an incredible sense to keep the house standing and to be a part of the conversation of the history,” recalls Nelan, whose two-bedroom home was built in 1912.

Nelan isn’t alone. Others who move into the neighborhood often don’t realize its roots as the segregation-era home to the Black laundresses, chauffeurs and butlers who worked for their Hyde Park neighbors. After all, what was left of Dobyville has been decaying for decades; the neighborhood is listed as one destroyed by the late 1960s. When what was then known as the Crosstown Expressway was built, splitting the neighborhood, there were even fewer reminders of Dobyville’s past.

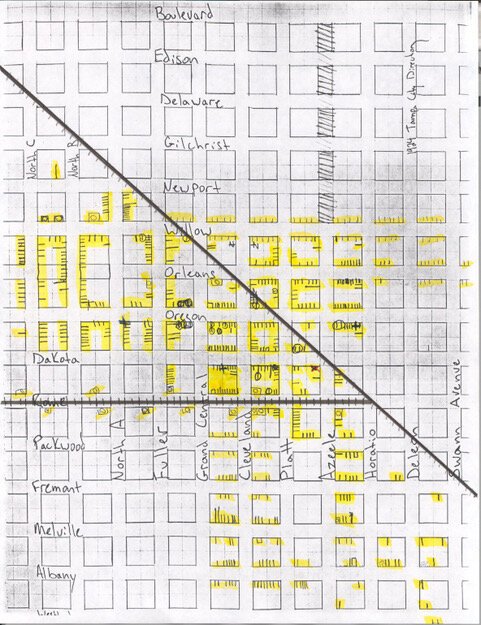

Couple that with the fact that the community has gone by an assortment of names: West Hyde Park, North Hyde Park, Courier City and Oscawana. And the borders to the industrialized area are somewhat fluid: from North Willow at Fig Street south to Swann, west to South Albany, north to Kennedy Boulevard, east to Rome, north to Fig and east to North Willow, according to Rodney Kite-Howell, director of the Touchton Map Library at Tampa Bay History Center.

Finding, preserving remnants of Dobyville

As development continues to change the landscape of the Tampa area, Nelan and her neighbors are taking action to preserve whatever is left. Through the Hyde Park–Spanishtown Creek Civic Association, they are asking the city of Tampa to extend the local historic designation to include a larger chunk of Hyde Park that recognizes Dobyville.

“It is one of the few areas in the overall area of Tampa that can be preserved,” says Reese Riggle, former civic association president. “It’s rare and it’s urgent because of the amount of development happening.”

Riggle, whose house at 312 S. Willow Ave. is also regarded as a historic Dobyville home, learned of its historic significance through Kite-Howell. He says he feels honored to live in a Dobyville home.

“I don’t know its individual history, unfortunately. I’d love to learn it,” says Riggle.

As a separate project, Hyde Park-Spanishtown Creek Civic Association members envision a park or other neighborhood feature to commemorate Dobyville’s past.

“We’d like to see a neighborhood space that honors the history of Dobyville. For example, a small park that includes community art celebrating the history of the neighborhood,” Nelan says.

The Dobyville area sprung up as a working and middle class neighborhood; about 10 percent of Black families living in the Tampa area lived there in 1927. One of the remaining landmarks is the old Seybold Bakery at 420 S. Dakota Ave., which once filled the neighborhood with the delectable aroma of fresh baked bread.

“It became symbolic of the neighborhood,” Kite-Powell, who researched the area through Tampa’s 1924 City Directory, points out.

Today, the bakery has been turned into condominiums and renamed Seybold Lofts. Among those who make their home there is Roger Copp, a founding member of the neighborhood’s civic association.

“Portions of the old elevator shaft remain and the interior brick walls in some of the units are clearly original. We can see footprints of workers in our concrete floors that are clearly from the original construction,” he notes. “The central hallway has photographs of the building from the 1930s or 1940s.”

Residents of Seybold Lofts’ single bedroom and multiple bedroom condos range in age from their 30s through retirement age. It’s a community where one neighbor can “borrow an egg or two” while cooking, Copp says.

Renewing a missed opportunity: Dobyville revisits historic designation

Kite-Powell believes extending Hyde Park’s historic designation to include Dobyville “would be a great credit and honor to those who created Dobyville.”

“I was on the city Historic Preservation Commission in the early 2000s and we [in my opinion] missed the opportunity to designate Dobyville,” Kite-Powell says.

He explains that the neighborhood history available at the time was incomplete, and adds, “this is finally the time to fix or to do what should have been done 20 years ago.”

In May, 2021, after renewed discussions about extending the local historic district, the civic association and the neighboring Historic Hyde Park Neighborhood Association made formal applications to designate Dobyville.

The application process

“Numerous boundary configurations have been discussed by the Historic Preservation Commission, but the most favored expands the northern boundary of the existing district, which currently is situated, for the most part, at De Leon Street, up to the Selmon Expressway,” says Dennis Fernandez, Tampa’s architectural review and historic preservation manager.

The Historic Hyde Park Neighborhood Association also asked to extend the district for a few blocks from De Leon to Horatio and from Boulevard to the Selmon Expressway, says its board member Del Acosta.

Acosta, who worked as the city’s historic district manager from 1996 to 2010, says the area wasn’t initially included in the local district when the state made the designation in the 1980s, due to a prevalence of slumlords and title issues.

Although the entire study area is in a National Register of Historic Places district, it lacks the added protective regulations afforded by a local historic designation. About 40 to 50 percent of homes in the proposed new local historical area were built before 1933, Fernandez says.

City officials say the issue of Dobyville’s historic designation is on the agenda for a 5:30 p.m. meeting April 13, at City Council chambers, 315 E. Kennedy Boulevard.

“If expansion of the Hyde Park Local Historic District is recommended by the commission, two public hearings before Tampa City Council will follow for final consideration,” Acosta explains. “Opportunity for public input is welcomed at all of the hearings.”

If approved, the area would face scrutiny by the city’s Architectural Review Commission to ensure new buildings are architecturally compatible with the rest of the neighborhood.

“We are pro-preservation, but we are not road blocking development,” says Aaron Albregts, the civic association’s president, who lives about one block outside of Dobyville.

He says at least 100 historically significant homes, including some outside of the Dobyville community, would be included with this proposed expansion.

“You can easily wash away some of the history,” he says. “That’s why we feel it’s important to approach development with a preservation mindset.”

Historical designation helps prevent erasure

An example of the erasure that can happen to older neighborhoods is what did happen to the 2.5-acre cemetery Doby founded in 1901 in an area east of Florida Avenue and south of E. Virginia Avenue, in the vicinity of Tampa Heights.

Zion Cemetery, the first recognized Black cemetery in Tampa, was erased by the projects subsequently developed there — until an investigation by the Tampa Bay Times revealed the truth, Tampa Housing Authority records show.

Doby sold the cemetery in 1907 to the Black-owned Florida Industrial and Commercial Co. and the property eventually passed hands to developers, Housing Authority records show. About 1.22 acres belongs to the Housing Authority, which relocated 32 families in 2019 after ground penetrating radar revealed anomalies believed to be intact coffins.

“The temporary memorial that’s in place now is educational materials that serve to mark the sacred site and illuminate the history of the site for passersby,” says Leroy Moore, the authority’s senior vice president and chief operating officer. “That memorial went up as soon as relocation was completed and is a wrap for the fence that protects this site until we develop the actual memorial park.”

The housing authority is slated to redevelop Robles Park Village, the last traditional barracks-style public housing project which opened to whites only in 1954, starting 2024. Work will be done in stages and take six or more years to complete. A Zion Memorial Cemetery Park also will be built concurrently as a separate project, Moore says.

“I think the record is quite clear that THA (as one of the three current owners) has done more to document, protect, preserve and honor Zion than any organization in this community,” Moore notes.

“And we continue to work with the community and the Zion Cemetery Preservation and Maintenance Society to ensure that Zion is respected and recognized as the final resting place for hundreds of pioneering African Americans despite century-long efforts to erase it and dishonor the contributions of those interred there.”

The city has been working closely with the Zion Cemetery Preservation and Maintenance Society since it was formed two years ago, and has helped obtain state and local grants, says Adam Smith, the city’s communications director.

“We look forward to assisting their efforts to appropriately memorialize Zion and recognize those who were buried there,” he says.

An important story to tell

Yvette Lewis, president of the Hillsborough branch of the NAACP, who has served on the Zion Cemetery Preservation and Maintenance Society as well as the Zion Cemetery Advisory Committee, would like to see more done to right the wrong.

“Zion still has a long way to go when it comes to correcting that wrong. You know the city definitely needs to step up and take some ownership of what happened,” she says. “It is time for the city of Tampa to tell our story … and right this wrong part of history.”

While she acknowledges the Housing Authority’s efforts, she says, “they could do more.”

“There’s always room to improve on what they are doing,” she says. “To me, what they’re trying to do is make it look pretty. Some parts of our history just aren’t pretty. Tell the truth; tell the story.”

Lewis applauds efforts to extend the historical designation and welcomes the opportunity for NAACP to be a part of it.

“I think it’s so important to tell the history of African Americans and what part they have played [in history],” she says. “I commend them for stepping out in front of this, and wanting to right this wrong part of history. So much of our neighborhoods have been erased all for the sake of progress.”

Meanwhile, residents of the Dobyville area and their neighbors continue to educate people about the community’s heritage: its older homes and their front porches. Its mature trees. Its alleys. Its shotgun style, long-and-narrow dwellings.

Walking tours of Dobyville illuminate the past

While awaiting historic designation, Dobyville is gaining recognition through neighborhood walking tours. Kite-Powell is scheduled to guide the second Dobyville walking tour — the first tour through the Historic Hyde Park Neighborhood Association, which celebrates its 20th season of historic Hyde Park home tours on March 5.

“The Dobyville neighborhood has had a lot of demolition over the last 20 years,” Kite-Powell notes, “but there are still some great examples of the homes that were and still are in the neighborhood.”

He says he will touch on the railroad that ran perpendicular through Hyde Park and the spur that was on Rome Avenue.

“I will do my best to highlight what is gone,” Kite-Powell says. That includes an old school and three churches.

Register here for the Hyde Park Home Tour, taking place March 5, 2022.

Also, the neighborhood associations will be discussing the historic designation at a 6:30 p.m. meeting on Thursday, March 31, at Kate Jackson Community Center.