Preparing for climate change: Pinellas County, local towns take steps to get ready

In the second in a series of stories about climate change, 83 Degrees Media explores how government officials in Pinellas and Hillsborough counties as well as more than two dozen municipalities are preparing for rising sea levels and the potential impact on infrastructure and neighborhoods.

Second in a series.

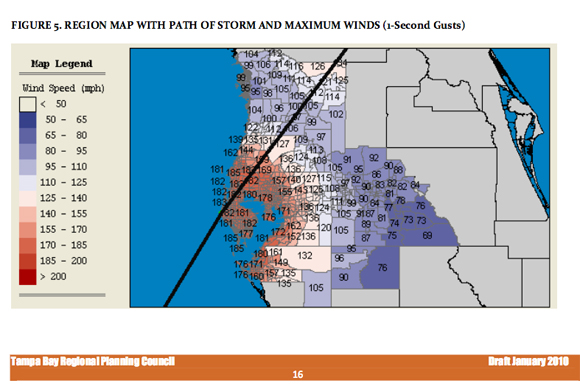

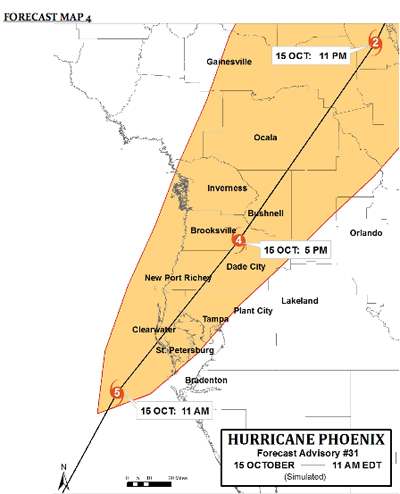

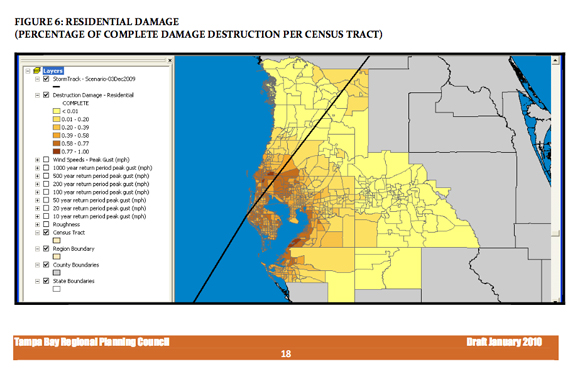

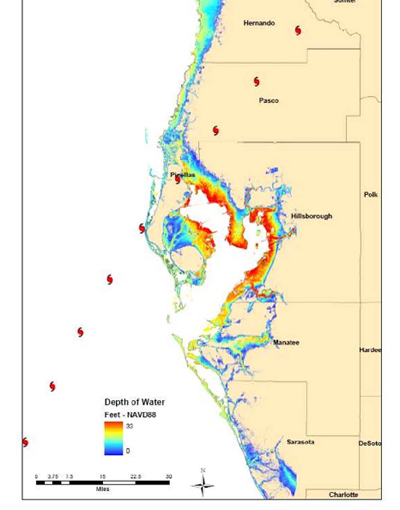

Picture this: It’s high noon on an October afternoon. The 45-mile wide eye of Hurricane Phoenix has just made landfall near Indian Rocks Beach. Spinning winds of 160 miles an hour, Phoenix pummels buildings and forces a 26-foot storm surge up Hillsborough Bay into Downtown Tampa. Floodwaters inundate the Pinellas peninsula; central St. Petersburg even becomes an island temporarily. The area’s bridges are wiped out. Millions lose power that won’t be restored for days or even weeks. Sustained hurricane-strength winds last for about 10 hours before the storm finally clears the region, headed northwest toward St. Augustine.

Hurricane Phoenix represents a worst-case storm event for the Tampa Bay region. Its journey is laid out in exacting, hour-by-hour details in the Tampa Bay Catastrophic Plan, dubbed Project Phoenix. The plan was created in 2010 to help the region’s governments and key institutions to understand — and prepare — for a once-in-a-lifetime natural catastrophe.

All told, a hypothetical Hurricane Phoenix could create upwards of $140 billion in damage to hundreds of thousands of homes and businesses across the Tampa Bay region. That’s an even bigger price tag than the $120 billion in losses caused by Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Loss of life would likely be severe, too, and the region’s road to recovery would be long and rocky.

Imagine these risks amplified by climate change, like higher sea levels or more extreme weather events. As 83 Degrees explored last week in its first in a series of stories on climate change, Tampa Bay area scientists and local government officials are already working together to better adapt the latest climate science to policymaking, with sea level rise being a major area of current focus.

As a peninsula on a peninsula, Pinellas County is exceptionally vulnerable to climate risks like sea level rise. Under a Hurricane Phoenix-like scenario, Pinellas County would see an estimated one-third of the region’s total financial losses — upwards of $57 billion in losses to property, or roughly equal to 80 percent of the value of its property tax base, according to the county’s most recent Local Mitigation Strategy, which is available online here.

Those staggering numbers are in part due to the particular storm track used for the Phoenix simulation, but also a reflection of Pinellas County’s unique geography, of which the Local Mitigation Strategy paints a clear portrait. Some 588 miles of coast ring the peninsula, which is largely flat save for a ridge that runs from north to south. Much of the county’s development has been on barrier islands, in the flood plain or on filled land.

Despite it’s small size, Pinellas County is also the single most densely populated county in the southeastern United States. It’s home to roughly 930,000 full-time residents and plays host to nearly six times that many annual visitors. The peninsula is largely built out, with aging infrastructure that will need increasing levels of upkeep and investment over the coming decades. And Pinellas County is home to 24 local governments, each with unique community needs and priorities.

Collaboration is key

While there can be no one size approach — or solution — to understanding Pinellas County’s vulnerabilities to climate change, a clear trend is emerging across the county today: Local governments of all shapes and sizes are building the know-how to make the region more resilient to the impacts of climate change. And they’re developing that knowledge collaboratively, across formal municipal boundaries.

Pinellas County officials, for example, will soon begin a three-year, county-wide sea level rise vulnerability analysis.

“We’ll look at the most critical infrastructure, identify hot spots where we need to focus intensively and determine what we need to do, can do and will do,” according to Kelli Hammer Levy, Pinellas County’s Natural Resources Division Manager, who is one of the project’s leaders.

Levy emphasizes that critical infrastructure doesn’t just include bridges, power plants, or water treatment facilities, but everything ranging from hurricane shelters and hospitals to coastal habitats and entire neighborhoods.

“Homes are critical infrastructure. Our Gulf Beaches are critical infrastructure,” she explains.

Officials plan to use a range of methods, including public input, to identify that critical infrastructure. From there, the project team will examine a wide range of measures that can reduce their risk exposure over time. As part of these efforts, the county will also develop a “full cost accounting” approach to examine the costs and benefits of various risk reduction measures, including both their direct up-front costs, along with the costs of not taking action. Such “costs of inaction” might range from the economic impacts of a short-term disruption in services to a give area after a storm, like the loss of a bridge, to a longer-term decline in the property tax base of neighborhoods in high risk areas.

The project is a partnership with all 24 Pinellas County municipalities, along with the Tampa Bay Regional Planning Council and Pinellas Metropolitan Planning Commission.

“The impacts of sea level rise will not recognize jurisdictional boundaries. The existing network of roads and utility infrastructure already transcends individual local government limits; flooding and inundation events do not respect county or municipal limits. Responding collaboratively to the collective challenge of sea level rise only makes sense,” Pinellas officials wrote in their grant application for the study.

The $300,000 study was one of five projects chosen by a county working group to receive funds from the Gulf Coast Restoration Trust Fund. The Fund was created through the RESTORE Act to distribute the fines and penalties collected after the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill to impacted communities, including Pinellas County. The study should begin once Pinellas County and the U.S. Treasury complete formalities associated with the grant award, according to Levy.

The planned Pinellas study will advance some of the same methods used in a Hillsborough County transportation vulnerability assessment completed in 2014. Funded by the Federal Highway Administration, that project looked at how different sea level rise, storm surge and inland flooding scenarios could impact the use of the most traveled coastal road segments in Hillsborough County, like Gandy Boulevard and the Memorial Highway. It also studied the cost-effectiveness of different approaches to minimize those risks, ranging from drainage improvements to constructing wetlands adjacent to roads. Preliminary findings from the study suggest that, under certain climate scenarios, there could be significant economic benefits associated with taking preemptive measures to retrofit some of the existing roads, while fewer benefits in the case of other roads.

The City of Clearwater is also undertaking its own vulnerability study. Last year, the city received a grant from the Florida Department of Economic Opportunity to participate in a new pilot program called the Coastal Resilience Vulnerability and Adaptation Pilot Series. Three cities — including Clearwater — are participating in a two-step process over the several months, first looking at their local climate vulnerabilities through a risk assessment and then identifying potential adaptation measures that might offset that risk.

The Clearwater pilot study, which is being managed by the environmental consulting firm Dewberry, has both a limited budget and timeline, and is scheduled to wrap by the end of 2016. That means it’s up the city to decide whether to use the project’s resources to take a broader look at multiple issues, or to dive deeper into one particular challenge, like how sea level rise may impact Clearwater Beach’s tourism business, according to Clearwater city Planner Kyle Brotherton.

Regardless of the approach that’s ultimately taken by the City of Clearwater, the intention is for the study to identify and prioritize “adaptation action areas” and measures that can be incorporated into the city’s planning strategy and development code. The state also hopes that the pilot will serve as a blueprint for other communities across Florida.

Designing a different approach

In St. Petersburg, the city is taking a somewhat different approach to climate change adaptation, weaving goals around sustainability and community engagement into several different facets of local government.

In August 2015, Mayor Rick Kriseman signed an Executive Order outlining several actions ranging from a commitment to pursue the U.S. Green Building Council’s LEED certification on all new and existing city buildings greater than 10,000 square feet in size to the creation and implementation of a new citywide climate action plan. In recent weeks, the city has been pursuing transportation alternatives, like a new ferry service to Tampa.

As the City of St. Petersburg’s Sustainability Coordinator, Sharon Wright is tasked with overseeing several of these efforts, and more broadly ensuring that the Mayor’s sustainability and climate resilience goals are incorporated into the city’s work in a comprehensive fashion. Wright is also spearheading efforts to obtain St. Petersburg’s certification under the STAR Communities program. The program helps cities to develop collective, community-powered approaches to sustainability, with an eye toward building a stronger community foundation to address climate changes over the long haul.

It’s not just the large local governments that are taking proactive steps to become more resilient to climate change and sea level rise. The small barrier island community of Treasure Island, for example, adopted more stringent building codes years ahead of state requirements, according to Paula Cohen, Director of Community Improvement.

“From a structural standpoint, rising water from climate change will clearly impact the foundations of buildings. That’s why we’ve raised them up,” Cohen says, referring to the “huge leap” the city took in tightening building requirements to reduce flood damage. Treasure Island requires that new residential structures be built at least two feet above base flood elevation, which refers to FEMA’s estimate of the height water could reach in a given floodplain during a 1-in-100 year flood.

Cohen concedes that sea level rise could pose serious challenges for the low-lying community over the long-term, where most homes and businesses are about four feet above sea level. “The hardest one for us will be the infrastructure,” says Cohen. One major area of concern is the town’s storm water system, which will become less effective at draining water off of properties and streets as sea levels rise. The current system relies on gravity to move water, the physics of which will be compromised by a higher base sea level and water table. Retrofitting that system could be an expensive proposition for the community of 7,000. And the built-out island’s limited open space provides few opportunities to make use of more natural water management solutions, like drainage ponds.

Treasure Island’s story reflects a common challenge shared by many smaller local governments that are constrained by a combination of their unique geography and relatively limited government resources. That’s in part why the Tampa Bay Regional Planning Council regularly hosts the One Bay Resilient Communities Working Group as a forum to help local governments and their community partners to share practical insights and reflect on lessons learned.

At February’s One Bay meeting, staff from the City of St. Petersburg shared how they’re incorporating FL Senate Bill 1094, a new legislative requirement that amends how local governments in coastal areas address flood risks in their comprehensive plans. It’s another one of many small, if multiplying examples of how local governments are increasingly working together to develop the institutional know-how they’ll need to respond to climate change over the long haul, both in Pinellas County and across the Tampa Bay area.

Next in our climate change series: We’ll look at how the global property insurance industry is taking steps to manage growing climate risks — and what that could mean for the Tampa Bay region. Comments? Contact 83 Degrees Media. Follow us on Twitter @83degreesmedia.

Links to 83 Degrees Media’s series of stories on climate change:

Part 1 — Tampa Bay Area scientists, policymakers plan for rising sea levels

Part 2 — Preparing for climate change: Pinellas County, local towns take steps to get ready

Part 3 — Is the global reinsurance industry making Florida more resilient to climate change, hurricanes?

Part 4 — Tampa Bay real estate boom and climate change: 5 big insights

Part 5 — Climate change: Across Tampa Bay, environmental organizations mobilize around sea level rise

Part 6 — Rethinking Tampa Bay’s water resources as the climate changes

Part 7 — Retrofitting Tampa Bay for climate change: From understanding to action