USF Leverages Arts, Sciences To Provide Better Healthcare

In a league with Harvard, Yale, the University of Miami and other big name academic centers, USF Health leads the way in using art to teach future doctors, nurses, physical therapists and public health professionals how to sharpen their visual observation skills to become better healthcare providers.

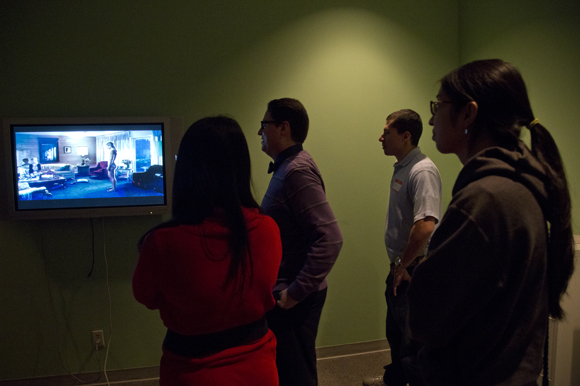

A small group of USF Health graduate students fall silent as they gaze at an enormous four-panel, floor-to-ceiling video installation of several women swimming underwater, a compelling and slightly eerie exhibit on display at the USF Contemporary Art Museum.

“What do you see?” “How does it make you feel?” “What do you think is going on?,” asks the student leading the group discussion of the exhibit: “Blood, Sea” by Janaina Tschape.

Another equally riveting installation, Pedro Reyes’ Imagine, also prompts an intense student discussion. In Imagine, Reyes has created musical instruments from weapons — thousands of revolvers, bullets and machine guns confiscated by the Mexican government. The musical instruments are all functional, including a xylophone that’s in perfect tune.

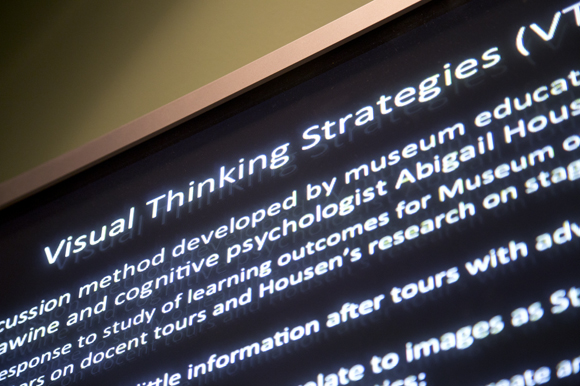

“What we’re doing here is teaching visual thinking strategies using art,” says Megan Voeller, associate curator of education at the USF Contemporary Art Museum, and program director of Art in Health, an innovative program that launched at the USF Tampa campus in 2012.

VTS or visual thinking strategy is a teaching method that “improves critical thinking, listening, communication and visual observation,” says Voeller. “It’s also about mindfulness and the ability to reflect and focus.”

The goal is to help future healthcare clinicians improve their observational skills, especially useful when making a patient diagnosis.

Medical student Julia Zhang says that as a science major, “it’s easy to focus on knowledge and book-based learning and forget to really observe the patient.” Participating in Art in Health provides an opportunity to “look at things from a different perspective.”

Public health student Adam Slotnick agrees. In a post on his Facebook page, he summarizes the lessons he’s learned so far: 1) make sure you examine items and issues from different perspectives; 2) don’t rush: slow down and work on the finer details; and 3) the importance of teamwork and listening to different points of view.”

So far between 60 and 70 graduate and professional students from USF Health have participated in the program, which is free and completely voluntary, not a class requirement, says Voeller, who championed the project with Margaret Miller, director of the USF Contemporary Art Museum, and Stephen Klasko, former USF Health VP and dean of the USF Morsani College of Medicine.

Now a year old, the program continues to be supported and guided by the current USF Health Sciences administration and faculty, including Aurora Sanchez-Anguiano, M.D., Ph.D., a faculty member in the USF College of Public Health.

“Observation is the key in all of the health sciences,” says Sanchez-Anguiano. “The idea is to encourage students to pause and study what is in front of them for a minute; not to make conclusions while they are observing.”

Existing arts and medicine initiatives at Harvard Medical School, the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Yale School of Medicine, and other major medical centers across the country serve as the inspiration for USF’s program, says Voeller. Last May, she flew to Boston to attend a Harvard session.

But the local Tampa program is moving in a novel direction, she says. “We’re building on what they’ve accomplished.”

Rather than limiting the experience to medical students only, the USF program is open to all disciplines within USF Health, including nurses, social workers, physical therapists and public health students.

And instead of focusing only on an art museum visit, USF students experience hands-on art activities and a session in movement. A music workshop is expected to be added to the line-up next year.

Merry Lynn Morris, a faculty member at the USF School of Theater and Dance, teaches the movement component of the Art in Health program. It’s a session that helps them gain a new perspective through a kinesthetic lens, she says.

“We are constantly moving through our environment and using our body to engage with it through gestures and postures,” says Morris, who is a doctoral candidate in dance at Texas Woman’s University and also teaches individuals with disability through REVolutions Dance.

“On a subconscious level, we are seeing and reading these cues, but often not directing our attention to what those cues are saying,” says Morris. “The body as a place of emotional and sensory intelligence is often under the radar and forgotten.”

Through the movement workshop, students become more attuned to what the body is doing physically and what it is telling them. It’s not only a way of looking at patients with more awareness, but also understanding what their own body is communicating to others, says Morris.

Posture and handshake are two good examples, says Morris. “We may not realize what our posture and handshake are communicating to other people unless we get feedback.”

In another exercise, students lay on the floor in a curled-up fetal position. “When I ask how does this position make you feel, some students have a hard time describing it,” says Morris. “I try to help them connect verbal skills to their nonverbal experiences.”

Dolores Coe, a former Ringling College of Art and Design faculty member, and Bruce Marsh, professor emeritus with the USF School of Art and Art History, are collaborating on the studio art workshop component of Art in Health.

Students meet in a drawing studio in the art department and they engage in a few exercises using charcoal, ink wash and color. But the objective is not to teach students how to draw, says Coe.

“We’re using art as a tool for seeing — they’re engaging in acute observation, learning to trust eye-hand coordination and seeing the relationship of different objects to each other,” says Coe.

In another exercise, students overlap color chips to learn more about how people perceive color and to begin to see subtle distinctions in color.

“It’s a quick immersion into an experience that emphasizes the importance of observation and really taking the time see the complete picture,” says Coe. “The biggest hindrance is to jump in knowing what you know as opposed to drawing what you see.”

Students are given a sketchbook to take with them so they can continue to observe and record their environment.

“Drawing, collecting things, journaling are all ways of observing the world with greater awareness,” says Coe. “We’re teaching them that observation is not passive, but a very active visual and intellectual experience. It encourages you to shake up your set patterns of thinking.”

Janan Talafer is a freelance writer in St. Petersburg, FL, who shares a home office with her dog Bear and two cats Milo and Nigel. Comments? Contact 83 Degrees.