Partner Partner Content Chinsegut Hill: An extraordinary view of history

The Chinsegut Hill Historic Site in Hernando County has witnessed Florida and national history from prehistoric people through the Civil War and Emancipation to the women's suffrage movement and the Great Depression.

Located at one of the highest points in the state, the Chinsegut Hill Historic Site in Hernando County has witnessed Florida and national history from prehistoric people through the Civil War and Emancipation to the women’s suffrage movement and the Great Depression. On weekends, the Tampa Bay History Center offers public tours of Chinsegut Hill for a journey back into history.

Brooksville is home to one of the highest points in Florida. At 269 feet, Chinsegut Hill has been stumping visitors with its name for 118 years. The key that unlocks that mystery goes back to 1904 and the Robins – the last family to own this pre-Civil War plantation.

Thousands of letters and journal entries written by Elizabeth Robins, her younger brother Raymond Robins and Raymond’s wife Margaret Drier Robins serve as a treasure trove of history. The hand-written letters and journal entries paint a vivid picture of life on the hill between 1904 and 1954, a transformational period in Florida’s frontier and the nation.

“There are thousands and thousands of letters between Elizabeth and Raymond, and Raymond and Margaret. I’m transcribing Elizabeth’s diaries. She wrote every day for about 60 years and I’m in 1932 right now,” says Brooksville Main Street Executive Director and author Natalie Kahler. “Reading their descriptions of daily life is fascinating. Just how they traveled – those aren’t things we typically think about. How they didn’t have electricity here until about 1933. There was a fire in 1926 because they had to light up every room with candles. So, you get a vivid picture of daily life in that time period because of how much they (the Robins) documented their lives.”

It’s that love of writing that’s helped local historians like Kahler and the team at the Tampa Bay History Center to tell the rich human stories of Chinsegut Hill. Located in Hernando County, there is evidence of human occupation stretching thousands of years.

“A lot of times when people come up here and see the house on the hill, they think of the family that lived here but we want to tell a much broader story than that,” says Tampa Bay History Center Saunders Foundation Curator of Public History Brad Massey. “We have archaeological evidence that Paleoindians passed through here from the archaeological digs done. For us, the story is a long one that stretches thousands and thousands of years and we want to tell as many of its human stories as we can.”

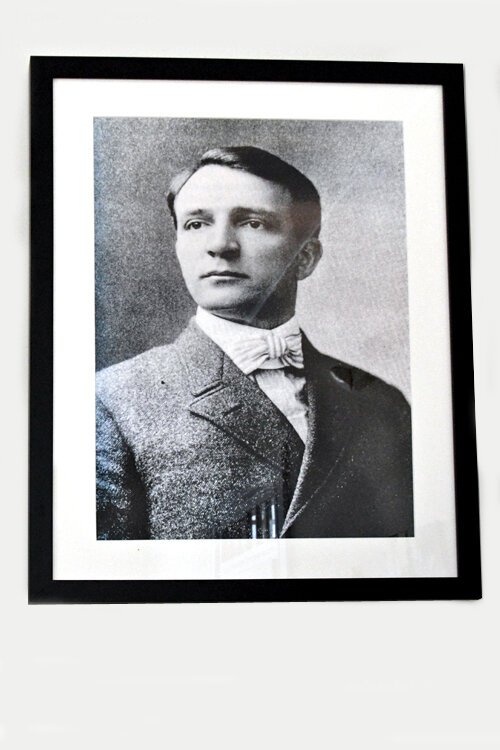

The most vivid pictures come from the Robins’ letters – sparked by a deep connection between brother and sister, Raymond and Elizabeth Robins. They lived most of their childhoods apart, sent away to live with different relatives because their father traveled extensively on business and their mother battled with mental illness.

In 1900, the bond between the siblings drove Elizabeth to venture to Alaska in search of her brother, who had moved there during the Klondike Gold Rush. To find him, she traveled by ship across the Atlantic Ocean, crossed the U.S. by train and rode a steamship up the Pacific Coast before finding Raymond in Nome, Alaska. By the time Elizabeth arrived, Raymond, a lawyer by trade, had swapped his days as a miner for ones ministering to the sick with yellow fever and serving as a social worker and preacher to the miners.

When Raymond convinced his sister to purchase the house in 1904, Elizabeth was an American actress living and working in London. The sale price was a reported $5,000. It had stood vacant for years following a tornado when the Snow family owned it.

“Elizabeth was still working in London so we have a lot of letters going back and forth between Raymond here in the U.S. and Elizabeth in London,” notes Kahler.

Raymond settled into a new life in banking and politics, married Margaret Drier, ran for U.S. Senator in Illinois and got involved in national politics, working on Theodore Roosevelt’s 1912 presidential campaign and serving as a diplomat. Over the years, his work and travels, as well as Elizabeth’s, helped fund major renovations at Chinsegut Hill before Raymond and Margaret returned to live there full-time in retirement.

All three Robins, Elizabeth, Raymond and Margaret, were kindred spirits in the women’s suffrage movement and socially progressive causes of the time. In a departure from social norms, they hired Fielder Harris, a former enslaved person at Chinsegut, to run the home and manage the sprawling property for them, as the official caretaker.

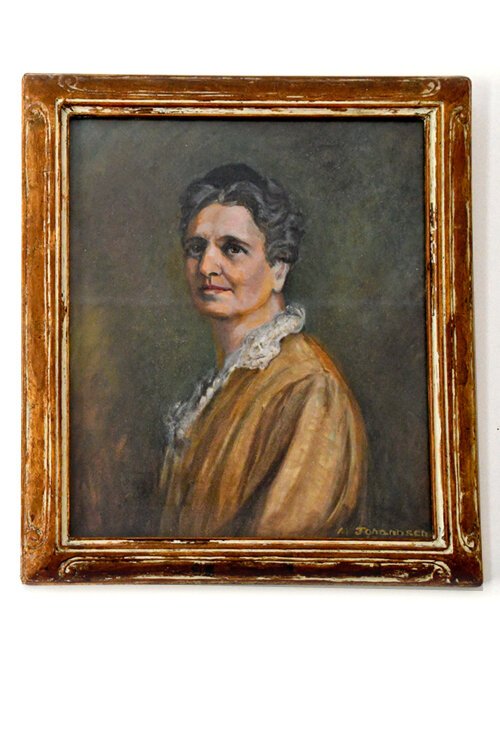

Margaret was also a prolific letter writer. She wrote to her husband Raymond extensively during her travels as the President of the Women’s Trade Union League.

“She was doing things with the labor movement with women and children,” says Kahler. “Raymond was doing things in the labor movement for men, but they were often in different places. So we have this gift of almost daily letters between them. Then you throw Elizabeth into that mix and you have long letters. A lot of times I can tell you what they ate for breakfast, lunch and dinner, and who they ate with.”

Once Raymond and Margaret Robins moved to Chinsegut Hill full-time in 1924, their letters to Elizabeth in London turned into detailed accounts of visits to the hill by luminaries of the time.

“That’s how we know all the people that visited here. That’s how we know about Thomas Edison, JC Penny and others because it’s in those letters,” says Kahler.

The house in Brooksville saw the likes of Helen Keller, the famous author, educator and political activist for the rights of people with disabilities. Thomas Edison too. By the time the legendary American inventor sat on Chinsegut’s majestic porch, he’d already designed the car battery for Henry Ford’s iconic Model T. Edison’s 1912 invention of the “self-starter” battery for Ford was, no doubt, among the topics of dynamic conversations, along with his incandescent light bulb and any one of the hundreds of patents he held on the way to his world record of 1,093 patents.

Among the luminaries traveling the shortest distance was likely Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings – the American writer and 1939 Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist credited with writing the precursor to today’s young adult fiction genre. “The Yearling,” and all of Rawlings’ short stories, were set in Florida’s frontier and written from the small town in Alachua County where she lived, approximately 65 miles north of Brooksville.

The stock market crash in 1929 and the Great Depression that followed, the transfer of Chinsegut Hill to the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the creation of the Civilian Conservation Corps camp on-site in the 1930s all happened while Raymond and Margaret lived there. It’s one property with an extraordinary view of Florida history.

Elizabeth died in England in 1952 but Raymond and Margaret lived at Chinsegut until the day they died. Margaret died first in 1945. Raymond died in 1954. Husband and wife are buried under the Altar Oak there, within perfect view of the tree house Raymond had built to watch the sunrise each morning. Chinsegut, pronounced Chin-SEE-gut, had lived up to its name during their lifetime and beyond. Interestingly, the name’s meaning was Raymond and his sister’s secret for years. (Watch the video at the top of this story to find out why.)

For more information, go to Chinsegut Hill.